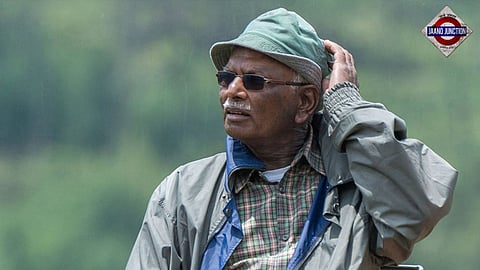

Asir Jawahar Thomas Johnsingh, also known as A J T Johnsingh, a distinguished Indian wildlife biologist and dedicated conservation activist, passed away in Bengaluru in the early hours of Friday, June 7, 2024. He was 78.

The ailing biologist-turned-activist died at around 1 am, according to a statement from his family. He leaves behind a rich legacy as a courageous environmental advocate and the strongest defender of the earth’s flora and fauna.

P O Nameer, a wildlife biologist and dean of the College of Climate Change and Environmental Science at the College of Forestry under Kerala Agricultural University, described Johnsingh’s passing as a significant loss for conservation in India, particularly in the face of opposition from vested interests.

“He was India’s foremost vertebrate ecologist. His key contributions to wildlife biology and conservation are manifold. He knew many tiger habitats in the country intimately, and the Sariska debacle involving the loss of all tigers from Sariska Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan was exposed partly due to Johnsingh’s effort. His effort was crucial in establishing a few tiger reserves in the country. Kalakkad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve (KMTR), at the far end of the Western Ghats, is one example,” said Nameer.

Born in Nanguneri on the southern edges of the Western Ghats in Tamil Nadu, Johnsingh was the child of educators. They often took him on weekend excursions to today’s KMTR in Tamil Nadu’s Tirunelveli district, a little distance away from Nanguneri.

The family’s engagement in agriculture and tree planting fostered his innate love for Nature. Johnsingh was also deeply inspired by Colonel Edward James ‘Jim’ Corbett’s timeless stories from India’s vast wilderness. The influence of his parents and Corbett led him to take up wildlife biology.

Between 1976 and 1978, Johnsingh gained international recognition for his groundbreaking fieldwork on free-ranging mammals in India, which included studying dholes (Cuon alpinus) in the Bandipur Tiger Reserve in Karnataka.

Although he briefly worked with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, Johnsingh returned to India in October 1981 to collaborate with the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS).

Subsequently, he joined the newly established Wildlife Institute of India (WII) in Dehradun as a faculty member and significantly expanded its focus and scope. He went on to become the dean of WII.

Even after retirement, he remained active in conservation organisations such as the Nature Conservation Foundation, WWF India, and the Corbett Foundation, remaining committed to preserving landscapes, habitats, large mammals, and Mahseer.

His research primarily centred on the Asian elephant, Asiatic lion, goral, Himalayan ibex, Nilgiri tahr, sloth bear, grizzled giant squirrel, and Nilgiri langur.

His enduring contributions to the conservation of endangered golden and blue-finned mahseers will always be remembered.

Johnsingh has authored over 70 scientific papers and more than 80 popular articles on wildlife conservation.

In recognition of his exceptional contributions, Johnsingh received the 2004 Distinguished Service Award for Government from the Society for Conservation Biology, the Carl Zeiss Wildlife Conservation Award 2004 for lifetime service to Indian wildlife, and the ABN AMRO Sanctuary Lifetime Wildlife Service Award in 2005. He is also a recipient of the Padma Shri, the fourth-highest civilian award in the country.

Johnsingh consistently identified himself as a dedicated wildlife enthusiast and emphasised that any threat to nature and wildlife deeply affected him.

Despite his profound affection for wildlife though, Johnsingh regarded himself as a practical conservationist, cautioning against excessive sentimentality that he believed hindered conservation efforts in the country.

In the past, he often mentioned Corbett, who deeply loved tigers but advocated for eradicating those who had become man-eaters, as his main inspiration.

JC Daniel, a BNHS researcher, was almost always the person Johnsingh named when asked about his mentors. Johnsingh first met Daniel in May 1971, while hiking in the Kalakkad hills.

At that time, Johnsingh had just completed his master’s degree in Zoology from Madras Christian College and started working as a professor of zoology at Ayya Nadar Janaki Ammal College, located in Sivakasi, southern Tamil Nadu.

Daniel encouraged him to record his observations of the environment and wildlife.

Daniel also helped him obtain a position as an assistant to Michael Fox, a global authority on canids (the dog family), in the Sigur Reserve Forests close to Mudumalai between 1973 and 1975.

Later, the influential writings of George Beals Schaller, an American mammalogist, scientist, conservationist, and author who had extensively written about numerous iconic mammalian species, had a greater impact on him.

In 1976, Johnsingh had a fortunate escape from a charging tiger while chasing dholes in Bandipur.

This occurred within three years of Bandipur’s formation as one of India’s first nine tiger reserves.

When he imitated the whistling sound of the dholes next to a group of sambar, a tiger emerged from the scrub and charged towards him, approximately 25 metres away. Using a tree as cover, he managed to get away.

Upon completing his research project on dholes, he dedicated it to his parents, acknowledging their role in nurturing his love and empathy for wildlife during his formative years.

He was the first person to obtain a clear image of a tiger roaming in Bandipur. Upon hearing the sound of the camera shutter, the tiger disappeared without a trace.

Johnsingh is responsible for many stunning photographs of wildlife, particularly elephants, which he has taken in various forest zones around India.

Despite his advancing age, he continued to hike through the woods. Until recently, he was known to navigate even the steep, rocky parts of the Western Ghats, regardless of his age and related health issues.

Johnsingh was not very happy with the way the environment and wildlife were treated by India’s politicians.

“I sincerely desire that we have successfully persuaded influential individuals, especially politicians, to have more robust support for wildlife preservation. Slow motion is a defining feature of how our beloved country operates,'” he once said when asked about conservation initiatives in the country.

When asked about his disappointments, he said, “We took a very long time to eliminate Veerappan, and it took even longer to imprison (wildlife poacher) Sansar Chand. Additionally, we have been discussing the crucial Chilla-Motichur elephant corridor in Rajaji National Park across the Ganges for more than twenty years.”

The late Johnsingh was a vocal advocate for adopting scientific approaches to address the escalating human-animal conflict in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve area, which encompasses forests in the states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Kerala.

In the case of conservation, he always wanted the greatest possible caution to be exercised in relocating forest dwelling people. Johnsingh believed relocation should only be done under very specific circumstances.

Protected areas like Anamalai Tiger Reserve and Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary have many dead teak trees due to elephant debarking. He once suggested that such trees could be harvested and sold, and the money could be deposited with conservation foundations and used for resettling people in Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary.

Johnsingh also left behind a remarkable legacy of training numerous forest officials in India and inspiring them to view conservation as a means to enhance the quality of life for people nationwide.

He mentored approximately 300 wildlife managers and 50 MSc Wildlife Science students and supervised 10 PhD students in India, leaving an indelible mark on forest management in the country.

That was when a conservationist once requested a message be delivered to young conservation officials. He advised them to avoid bitterness and destructive rivalry, as they waste time, energy, and resources.

“Some bright students and devoted forest officer trainees are my biggest legacy, but sadly, bureaucracy frequently restricts their freedom. I may be remembered as genuinely interested in practical conservation and the welfare of students and people with low incomes on the land. One example of practical conservation I have in mind is in the beautiful district of Coorg, or Kodagu in Karnataka, where people may be legally allowed to hunt a prescribed number of wild pigs every year. Still, no one should poach barking deer, sambar, and gaur, which will make the enchanting landscape of Coorg immensely richer,” Johnsingh said once.

“Nature is a great teacher. Allow your natural curiosity to take the lead. Be in good physical shape. It would help if you read everything you can find about the mysteries Nature offers. Be involved in conservation efforts and collaborate with people who share similar beliefs and ideals. Understand how to work with the authorities and persuade them to take appropriate actions that promote the protection of Nature,” he wrote once.